News

Who You Gonna Call?

Published November 08, 2007

By nature, emergencies are fast-paced and unpredictable events, often requiring rapid and accurate information to turn tragedy into triumph. Recently, emergency responders-including San Diego fire fighters and the American Red Cross-have discovered that the resources and expertise of the San Diego Supercomputer Center at UC San Diego can help meet their needs for quick, reliable, and up-to-date information in times of crisis.

SDSC experts are answering these calls through innovative data cyberinfrastructure technologies designed to respond to a wide range of emergencies, from earthquakes, hurricanes, tornadoes, and fires to attacks on the Internet. So, when a crisis hits and people ask, "Who you gonna call?" the answer may come as a surprise.

|

| FIGHTING THE HORSE FIRE

The first day of the fire on July 3, 2006 as seen from an HPWREN camera on Lyons Peak in San Diego County looking east. At the request of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, HPWREN set up a high-speed wireless link to a remote Incident Command Post, providing crucial information not otherwise available in the remote area. Photo: HPWREN. |

On the front lines of a fire, everything is heat and smoke. As conditions change, fires can turn, jump containment lines, accelerate faster than a man can run, or "blow up" in a violent conflagration. In such situations, firefighters need to know as much as possible about dynamically changing factors including humidity, wind, hotspots, vegetation, terrain, and allocation of manpower and equipment. They need access to a huge volume of data, which can't easily be relayed deep into the backcountry of San Diego County by radio or cell phone.

Luckily, SDSC networking researcher Hans-Werner Braun, one of the architects of the early Internet, has just what they need. Braun's ongoing research project is the National Science Foundation-funded High Performance Wireless Research and Education Network (HPWREN), a high-speed digital wireless backbone in San Diego, Imperial, and Riverside counties developed in partnership with UCSD's Scripps Institution of Oceanography and San Diego State University. The network allows high-speed data transmission into remote areas usually connected only by radio.

Braun's HPWREN was already involved in data transmission for research projects in several scientific fields when he approached the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CALFIRE) for permission to put transmission equipment and cameras on fire towers to extend the network.

"Once they saw our cameras they began wondering how they could use them," he said.

What followed was a collaboration in which Braun not only connected HPWREN to distant CALFIRE firefighting bases, but also dropped onto mountaintops during emergencies to erect temporary towers to link up specific hard-to-reach areas hit by a fire.

The network, which carries data at up to 45 megabits per second-about 30 times faster than a DSL line-can transmit real-time imagery from ground, air, and satellites. Firefighters can use this data to accurately map where the fire is, where it's moving, and where they need to focus their efforts. The value of the cameras and network was first proven in the 2003 Coyote Fire when detailed reports and images were sent to command posts, and CALFIRE headquarters in Sacramento could get timely, accurate updates to better manage firefighting efforts from afar. Since then, Braun and his colleagues have set up temporary links during six different fires.

"It's applications like this that keep HPWREN interesting for us," said Braun.

|

| SAFE AND WELL

Hurricane Katrina left thousands of people cut off from family and friends, and in collaboration with the American Red Cross and others SDSC provided advanced data technologies to reconnect people in the wake of this diaster. SDSC now hosts the Red Cross Safe and Well website. Photo: American Red Cross. |

Hurricane Katrina was a disaster made far worse by a lack of data. The government remained unaware that levees had broken until many hours after the event. The head of the Federal Emergency Management Agency surmised that everything was okay because a CNN newscast showed a dry French Quarter (one of few areas above sea level).

In the confusing aftermath, storm survivors were spread far and wide, unable to connect with family and friends. In an effort to help, many people created websites where refugees could post information about themselves. However, there were too many different websites, and people couldn't find the information they needed.

"What was needed was a way to integrate the information from all these sites," said Chaitan Baru, SDSC Distinguished Scientist and an expert in data technologies.

The Red Cross contacted Baru because his group at SDSC had essentially done this job before, using computer algorithms to find bioinformatics information spread across many websites and integrate it into one database. "The big difference in Katrina was that the data was much messier," Baru said. "The data was very 'noisy,' in all different formats and often incomplete and with errors."

Baru and his colleagues set up a data-cleaning "factory," inventing automated workflows that organized the data the Red Cross sent them. "Our team jumped in and put in long hours, from morning to night," Baru said. "We learned what you can do if you get a rush of noisy data and have to clean it up fast." Once they had cleaned it up, the data was handed off to Microsoft, which had volunteered to host the site where the integrated information was initially posted.

As a result of the Katrina experience, the Red Cross saw the need for a permanent website to help people connect following any type of sudden emergency, from a hurricane or tornado to an earthquake. Having worked closely with SDSC during Katrina, the Red Cross saw the center as a good environment to host the program, named the Safe and Well website.

"The Katrina website involved ten different vendors, each doing a different part of the job, but we're able to offer integrated capabilities in one location," Baru said. "Whatever problems came up, we had a range of people with the expertise to deal with it. It's really hard for industry to put this sort of effort together at a fast pace."

This expertise also allowed the SDSC researchers to add new features to empower emergency personnel. "It turns out that visualization is a key capability," Baru said. "We can put information on Google maps to let emergency workers see that a lot of people are moving into a certain area, so they know they had better move resources there."

For Baru, there was another important reason why SDSC was a perfect place to host the Safe and Well website. "We're a federally funded center, and this is integral to our mission," he said. "The notion of public service is built into what we do."

|

| WITTY WORM GOES GLOBAL

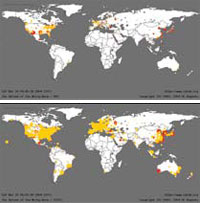

CAIDA researchers used the "UCSD Internet Telescope" to visualize the rapid global spread of the Witty Worm from the US to Asia and Europe in March 2004, with most major cities affected in just over two hours. Red locations were infected within the first 60 seconds; yellow locations after 60 seconds. Image: Colleen Shannon and David Moore, CAIDA. |

In the Information Age, computing and data transmission are critical to society. Computer viruses and worms, sometimes just a nuisance, at other times pose real risks to the Internet and other critical information infrastructure.

"Malicious worms and viruses can destroy files and cause major losses in productivity, even potentially bringing down 911 centers or hospitals," said Colleen Shannon, a researcher with SDSC's Cooperative Association for Internet Data Analysis (CAIDA) who works with SDSC researcher David Moore on the project. In collaboration with colleagues at UCSD and elsewhere and large Internet service providers, they have developed effective tools to track computer worms and warn people whose machines are infected.

When a worm first begins to spread, computer experts often call CAIDA first. "We're well known in the community, so we're given data to look at and analyze," Shannon said. Internet worms can spread to hundreds of thousands or millions of machines within hours, and catching them and stanching the infection requires the group to jump on the problem at any time of day and work quickly.

CAIDA can't stop an attack, but they can track it, determine the kinds of machines vulnerable to attack, and often tell people that their machines have been infected so that they can take countermeasures.

"We're like a hospital-we don't stop you from getting sick but we can help take care of you when you are sick," said Shannon.

Tracking the worms can take CSI-type sleuthing. In addition to gathering their own data, Internet service providers sometimes give the researchers log files that indicate a worm is spreading. "We can look at these files and track the geographic spread of the worm-who is infected and who is not, what kinds of machines are infected-and then distribute that information to network security personnel," Shannon said.

The group has come up with clever methods to follow the worms. When the Code Red worm struck in 2001, they used a tool called the UCSD Network Telescope, which relies on the fact that many Internet addresses are not used-they are either unassigned or belong to machines that are mostly idle. Most legitimate traffic is directed to the minority of real addresses, while malicious codes spread themselves to all of the Internet address space by selecting addresses randomly. If a machine is sending scattershot messages to unused IP address all across the Internet, chances are that this machine is infected.

CAIDA passes along information about infected machines to Internet service providers and network administrators, who let the users know their machine is likely infected. At that point, however, things are out of the hands of Shannon and her colleagues: users have to apply patches and disinfect their own machines.

"Sometimes we're quickly able to demonstrate how widespread a virus is and convince people to apply patches before they are infected, to wake them up from the mindset of 'It will never happen to me.'"

|

| SUPERCOMPUTING ON DEMAND

SDSC's innovative OnDemand system gives researchers rapid results in event-driven science such as this "virtual earthquake" movie that shows ground motion waves radiating from an earthquake event in Southern California. Image: ShakeMovie. |

When an earthquake greater than magnitude 3.5 strikes Southern California, a special supercomputer at SDSC speeds into action. Pushing aside jobs currently being processed, the computer analyzes data from earthquake sensors throughout the area, and within less than 30 minutes produces a 3-D "movie" that shows how the shaking spread through the region. The movies are made as part of the ShakeMovie project of the Near Real-Time Simulation of Southern California Seismic Events Portal led by computational seismologist Jeroen Tromp at Caltech.

The movies of the earthquake simulation can be created so quickly due to the recent installation of SDSC's OnDemand supercomputer, set up so that non-critical jobs can be put on hold when an emergency arises, said Anke Kamrath, director of User Services at SDSC.

The movie gives people an easily understandable picture of how the shaking took place, and Kamrath envisions many other applications of the OnDemand supercomputer useful to emergency responders.

"Right now we're using this for earthquakes, and people are making plans to use this capability for things like storm path prediction for hurricanes and tornados," Kamrath said.

Kamrath points out that when a storm, flood, earthquake or other disaster hits an area, existing maps are often useless. "Roads and bridges that show up on maps may in fact be gone," she notes. Much more useful are real-time images from satellites and virtual-reality-3-D mapping that shows the present state of affairs. "Emergency responders want to be able to look at current satellite imagery and do a virtual fly-through of what's actually happening after the disaster," she said.

Also extremely useful will be maps layered with color-coded information that can give emergency responders information at a glance about important factors like rainfall, flooding, and population movements. Constructing such real-time imagery and computer representations requires massive computing power, only possible if a supercomputer like OnDemand is immediately available to crunch through the mountains of data.

The need for an on-demand supercomputer is just one more example of how facilities like SDSC are introducing new capabilities to offer vital help in emergencies. In turn, the researchers are learning, the ability of firefighters, police, and rescue workers to access the right data quickly will dramatically transform how they can do their jobs and how many people will be saved during emergencies in the future.

"This is fundamentally changing emergency response," Kamrath said.

Christopher Vaughan has written numerous books and articles on science and medical topics. He lives in the Bay Area.

Categories

Archive

Related Links

Red Cross Safe and Well https://disastersafe.redcross.org/

CAIDA http://www.caida.org/

OnDemand Supercomputer http://www.sdsc.edu/us/resources/ondemand/