News

Studies Suggest New Key to “Switching Off” Hypertension

Published July 21, 2013

|

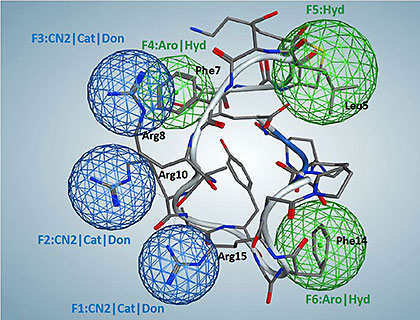

Catestatin-mimic pharmacophore model. Pharmacophore centers correspond to hydrophobic residues Leu5, Phe7, and Phe14; and positively charged residues Arg8, Arg10, and Arg15. Green circles represent hydrophobes and aromatic/hydrophobic features, while dark-blue circles represent NCN+ groups/cations/H-bond donors. Ribbon diagram and three-dimensional residue structures belong to superimposed catestatin. Image courtesy of Valentina Kouznetsova, UC San Diego. |

A team of University of California, San Diego researchers has designed new compounds that mimic those naturally used by the body to regulate blood pressure. The most promising of them may literally be the key to controlling hypertension, switching off the signaling pathways that lead to the deadly condition.

Published online this month in Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, the scientists studied the properties of the peptide called catestatin that binds nicotinic acetylcholine receptors found in the nervous system, and developed a pharmacophore model of its active centers. They next screened a library of compounds for molecules that might match this 3D “fingerprint”. The scientists then took their in-silico findings and applied them to lab experiments, uncovering compounds that successfully lowered hypertension.

“This approach demonstrates the effectiveness of rational design of novel drug candidates,” said lead author Igor F. Tsigelny, a research scientist with the university’s San Diego Supercomputer Center (SDSC), as well as the UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center and the Department of Neurosciences.

“Our results suggest that analogs can be designed to match the action of catestatin, which the body uses to regulate blood pressure,” said Daniel T. O’Connor, a professor at the UC San Diego School of Medicine and senior author of the study. “Those designer analogs could ultimately be used for treatment of hypertension or autonomic dysfunction.”

The research may lead to a new class of treatments for hypertension, a disease which affects about 76 million people, or about one in three adults, in the United States, according to the American Heart Association. Untreated, it damages the blood vessels and is a leading risk factor for kidney failure, heart attack, and stroke.

Despite being a common and lethal cardiovascular risk factor, hypertension remains only partially controlled by current antihypertensive medications, most of which have serious side effects. Specifically, the SDSC/UC San Diego researchers targeted the hormone catestatin for therapeutic potential. Catestatin acts as the gatekeeper for the secretion of catecholamines – hormones that are released into the blood during times of physical or emotional stress. A drug that mimics the action of catestatin would thus allow people to control the hormones that regulate blood pressure.

Based on earlier studies of the structure of catestatin, O’Connor, Tsigelny, and their colleagues figured out which residues of catestatin are responsible for binding to the nicotinic receptor – similar to mapping how the ridges on a key fit into a lock. They created a three-dimensional model of the most important binding centers – the pharmacophore model. Then they screened about 250,000 3D compound structures in the Open NCI Database to select ones that fit this fingerprint of active centers. They discovered seven compounds that met the requirements, and tested those compounds in live cells to gauge their effects on catecholamines. Based on their findings, they tried one compound (TKO-10-18) on hypertensive mice, and showed that this compound produced the same anti-hypertensive effect as catestatin.

“Analysis of the catestatin molecule yielded a family of small organic compounds with preserved potency and pathway specificity,” said Valentina Kouznetsova, PhD, an associate project scientist at SDSC and the UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center. “Further refinement of our model should lead to the synthesis and development of a novel class of antihypertensive agents.”

Authors include SDSC’s Tsigelny, O’Connor, and Kouznetsova, as well as Nilima Biswas and Sushil K. Mahata, of UC San Diego’s Departments of Medicine and Pharmacology.

About SDSC

As an Organized Research Unit of UC San Diego, SDSC is considered a leader in data-intensive computing and cyber-infrastructure, providing resources, services, and expertise to the national research community, including industry and academia. Cyber-infrastructure refers to an accessible, integrated network of computer-based resources and expertise, focused on accelerating scientific inquiry and discovery. SDSC supports hundreds of multidisciplinary programs spanning a wide variety of domains, from earth sciences and biology to astrophysics, bioinformatics, and health IT. With its two newest supercomputer systems, Trestles and Gordon, SDSC is a partner in XSEDE (Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment), the most advanced collection of integrated digital resources and services in the world.

Media Contacts:

Cassie Ferguson, SDSC Communications

casferguson@gmail.com

Jan Zverina, SDSC Communications

858 534-5111 or jzverina@sdsc.edu